Placebos as “meaning responses”

We define the meaning response as the physiologic or psychological effects of meaning in the origins or treatment of illness; meaning responses elicited after the use of inert or sham treatment can be called the “placebo effect” when they are desirable and the “nocebo effect” when they are undesirable…

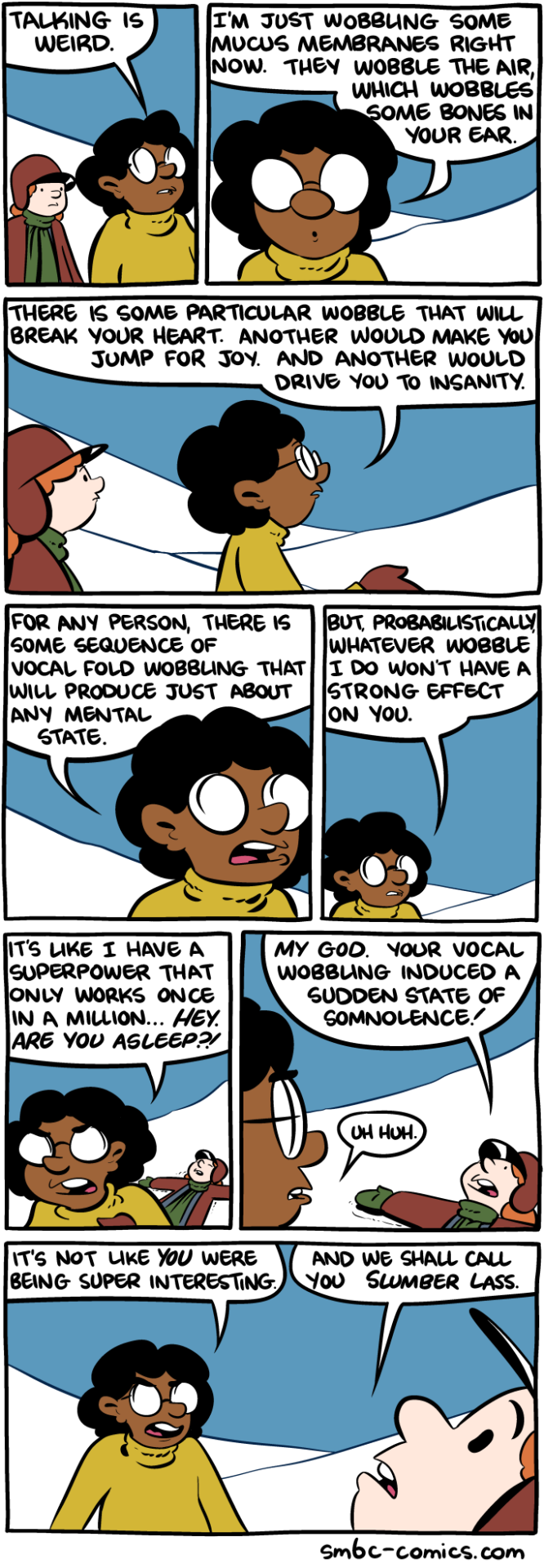

Insofar as medicine is meaningful, it can affect patients, and it can affect the outcome of treatment. Most elements of medicine are meaningful, even if practitioners do not intend them to be so. The physician’s costume (the white coat with stethoscope hanging out of the pocket), manner (enthusiastic or not), style (therapeutic or experimental), and language are all meaningful and can be shown to affect the outcome; indeed, we argue that both diagnosis and prognosis can be important forms of treatment.

— Daniel E. Moerman and Wayne B. Jonas, Deconstructing the Placebo Effect and Finding the Meaning Response, The Placebo: A Reader

Ted Kaptchuk on “legitimate healing”

Besides clinical and scientific value, the question of enhanced placebo effects raises complex ethical questions concerning what is “legitimate” healing. What should determine appropriate healing, a patient’s improvement from his or her own baseline (clinical significance) or relative improvement compared with a placebo (fastidious efficacy)? As one philosopher of medicine has asked, are results less important than method? Both performative and fastidious efficacy can be measured. Which measurement represents universal science? Which measurement embodies cultural judgment on what is “correct” healing? Are the concerns of the physician identical to those of the patient? Is denying patients with nonspecific back pain treatment with a sham machine an ethical judgment or a scientific judgment? Should a patient with chronic neck pain who cannot take diazepam because of unacceptable side effects be denied acupuncture that may have an “enhanced placebo effect” because such an effect is “bogus”? Who should decide?

— Ted Kaptchuk, The Placebo Effect in Alternative Medicine: Can the Performance of a Healing Ritual Have Clinical Significance?, The Placebo: A Reader

Fabrizio Benedetti on the neurobiology of placebos

Here is Fabrizio Benedetti, professor of physiology and neuroscience at the University of Turin Medical School, giving an introduction to the neurobiology of placebo effects. This gets into technical details of chemical names and brain anatomy, but a lot of it is also stated in a more general, accessible way.

I was especially interested in their discussion of which conditions are more influenced by placebo effects (pain, anxiety, Parkinson’s), and Benedetti’s distinction between conscious/expectation effects and unconscious/conditioning effects. This is my first encounter with the idea that different kinds of rituals can affect different systems in the body.

This is also my first time thinking about Pavlovian conditioning as a type of placebo response, and it is giving me ideas about ritual magick. I mostly think about meaning and significance as things that give rituals power and have effects on my body, which would fall under Benedetti’s conscious, expectation-based effects. It makes a lot of sense to me that repeating rituals could make them more potent, both because of the conscious effect of familiarity and expectation, and perhaps also because my body is being conditioned to respond in ways that I’m not conscious of.

Placebos as a science of rituals and spells

In exploring possible meanings of “critical magick”, I find myself collecting perspectives on magick from many different fields, many ways of knowing. Placebo researchers use the words “magic” and “ritual” more than you might expect from scientists. Here is Ted Kaptchuk, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, giving an introduction to placebo studies. He explains a definition of placebos not as fake treatments, but rather as the impact of all the cultural and relationship stuff that happens along with treatments.

‘Placebo effects’ is a way of quantifying and measuring everything that surrounds pills and procedures, mainstream or alternative. They’re about the rituals, the words, the engagements, the costumes, the diplomas, and those special things you get when you go to a healer.

Andy Warhol on rituals, basically

Actually, I jade very quickly. Once is usually enough. Either once only, or every day. If you do something once it’s exciting, and if you do it every day it’s exciting. But if you do it, say, twice or just almost every day, it’s not good any more.

A ritual template from sex magic

Perhaps strangely, the rituals I have found most accessible and least scary are sex rituals. Partly because I’ve only done them with people I’m very close with, and partly because sex rituals have a big advantage if you want to find rituals that don’t feel like going through superstitious motions. Your body will let you know whether your ritual for creating sexual connection and ecstasy is powerful or not.

Longtime sex activist Barbara Carrellas, in her book Urban Tantra (byoa, as always), gives a series of steps and associated intentions for sex rituals that I have been applying to sex for almost ten years:

- Set the stage (to prepare the space)

- Chill out (to relax and get present)

- Warm up (to engage your body)

- Come together (to get connected)

- Rock and roll (to enjoy some ecstatic activities)

- Afterglow (to cool down and bask)

I really appreciate the order of stages 1-4: space, mind, body, connections. They build on each other in practical as well as symbolic ways.

Divination as strategic observation

Auguries and sacrifice: crude tools of toothless practitioners. Or so her mother said, even as she’d rehearsed Hild in every variation. But she said, over and over, there was no power like a sharp and subtle mind weaving others’ hopes and fears and hungers into a dream they wanted to hear. Always know what they want to hear– not just what everyone knew they wanted to hear but what they didn’t even dare name to themselves. Show them the pattern. Give them permission to do what they wanted all along.

Hild is Nicola Griffith’s historical novel about the childhood of St. Hilda of Whitby, and it goes deep into how Hild(a) could have become what she was: an advisor to kings. In the 600s, advising a king mostly looked like fortunetelling and making wishes come true, so this is in a lot of ways a non-supernatural story about a very successful witch.

The book presents divination as a material skill. Rather than contacting the spirit world, Hild learns to read things that other people can’t. Why the birds are nesting low in the trees, what makes someone stand straighter, how wealth is going to shift, or, more literally, gossip in foreign languages, and what it all reveals about opportunities, motives, and risks. It reminded me of Dune or Sherlock Holmes, from the perspective of a girl. Obviously I love this– forest whispering and social intuition are the kind of witch skills I want to have.

Personification of the unconscious

Perhaps the subconscious of the Roman soldiers [, who had seen a vision of the god Pan showing them a safe place to cross a river,] was perfectly capable of making lightning calculations as to the river’s depth and the speed of its current, but was unable to pass it to their conscious minds in the direct manner that modern brains employ. Could it be that the visions of gods or supernatural figures that populate our histories are projections, messages from an unconscious that was at the time unable to communicate in any other way?

— Alan Moore, From Hell (back matter)

I like to think about Alan Moore’s projection idea when I work with visualizations and self-guided meditations. Could it be that apparitions are a pretty good way to talk to your own subconscious?

The first visualization I learned, and still the main thing I do, is to ask to meet a particular character (a dream teacher, a life coach, a friend) and then ask that character questions. At first, all I could do was act out the scenes with my usual conscious mind, but with practice I am much more able to wait quietly until these figures take their own forms, and give me sometimes surprising answers. It feels more and more like asking my unconscious mind to meet up for a chat, and more and more like a mindfulness exercise where my task is to let my conscious mind get still.

The deepest insight I can currently get from these dream figures is on the level of “what should I ask you?” or “why am I anxious?”. In the beginning the answers were often things I knew consciously but didn’t want to admit. These days the answers are more opaque and strange, more like a dream. I am curious whether I could practice enough to get (correct) answers to questions like “where did I forget my keys?” or “is my body healthy?”– things I might know on some level, but can’t think of in my conscious mind. It occurs to me that when I ask to meet someone in a visualization, I should try asking for my unconscious mind itself.

The Bible as a colonial grimoire

As Christianity spread across the European colonies natives wondered whether the Bible was the occult source of power of the white colonizers. Amongst the peoples of parts of Africa, South America, the Caribbean, and the South Pacific, anthropologists have found a widespread notion that the white man deliberately withheld the full power of Christianity in order to keep them in a state of subjugation. This was not necessarily achieved by restricting literacy, but by deliberately withholding some of the true Bible and therefore the complete key to wisdom, knowledge, and consequently power. In the Caribbean today, for instance, the Bible is considered by some as an African divine text appropriated and controlled by Europeans. When asked why he accepted the Bible but not Catholicism, a worshipper of the Trinidadian spirit religion of Orisha explained, ‘The Bible came from Egypt; it was stolen by the Catholics who added and removed parts for their own purposes.’